The Russian annexation of Crimea and armed conflict over Donbas have brought these regions into the limelight. At the same time, there is a lack of sufficiently complex analysis of Ukrainians’ attitudes toward Donbas and Crimea and their understanding of what is happening there. Traditional analyses of Ukrainian attitudes divide the country into large macro-regions, resulting in a misleading grouping of diverse oblasts (Ukraine’s administrative regions). This 'Donbas and Crimea In Focus' module changes that optic, presenting data by oblast for a more nuanced view of attitudes and understanding throughout Ukraine.

The Russian annexation of Crimea and armed conflict over Donbas have brought these regions into the limelight. At the same time, there is a lack of sufficiently complex analysis of Ukrainians’ attitudes toward Donbas and Crimea and their understanding of what is happening there. Traditional analyses of Ukrainian attitudes divide the country into large macro-regions, resulting in a misleading grouping of diverse oblasts (Ukraine’s administrative regions). This 'Donbas and Crimea In Focus' module changes that optic, presenting data by oblast for a more nuanced view of attitudes and understanding throughout Ukraine.

In the process of granting the Ukrainian Orthodox Church autocephaly and during the recent presidential and parliamentary election campaigns, the question of religious self-identification emerged at the center of nation- and state-building processes in Ukraine. The 'Religious Revolution' module analyzes recent changes in Ukraine’s religious landscape. It presents sociological survey data about Ukrainians’ religious beliefs, attitudes, and practices. In the web map, data from three surveys (2013, 2017, 2019) can be used to acquire a visual representation of regional religious differences and changes over time.

In the process of granting the Ukrainian Orthodox Church autocephaly and during the recent presidential and parliamentary election campaigns, the question of religious self-identification emerged at the center of nation- and state-building processes in Ukraine. The 'Religious Revolution' module analyzes recent changes in Ukraine’s religious landscape. It presents sociological survey data about Ukrainians’ religious beliefs, attitudes, and practices. In the web map, data from three surveys (2013, 2017, 2019) can be used to acquire a visual representation of regional religious differences and changes over time.

The 'History and Identity' module as part of the MAPA program aims to contribute to a reconceptualization of regionalism in Ukraine. The project uses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology to map and analyze sociological data. Mapping data on the region (oblast) level avoids arbitrary scaling into predefined macro-regions, and allows researchers to explore and explain intraregional and cross-regional differences and similarities in the changing social and political context of 2013 and 2015 Ukraine. The “History and Identity” project contributes to the comparative cross-regional analysis of identities and historical memory in today’s Ukraine using the most recent sociological survey data.

The 'History and Identity' module as part of the MAPA program aims to contribute to a reconceptualization of regionalism in Ukraine. The project uses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology to map and analyze sociological data. Mapping data on the region (oblast) level avoids arbitrary scaling into predefined macro-regions, and allows researchers to explore and explain intraregional and cross-regional differences and similarities in the changing social and political context of 2013 and 2015 Ukraine. The “History and Identity” project contributes to the comparative cross-regional analysis of identities and historical memory in today’s Ukraine using the most recent sociological survey data.

The language issue in Ukraine has long historical roots, and even after Ukraine’s independence it remained in the center of the nation- and state-building processes. Different political parties often used language tensions for political mobilization or to draw imagined regional divisions. It also served as an important marker in defining cultural and national identities or allegiances. Through the 'Language' module, we can explore and visualize changes in the sociolinguistic landscape of Ukrainian society between 2013 and 2017.

The language issue in Ukraine has long historical roots, and even after Ukraine’s independence it remained in the center of the nation- and state-building processes. Different political parties often used language tensions for political mobilization or to draw imagined regional divisions. It also served as an important marker in defining cultural and national identities or allegiances. Through the 'Language' module, we can explore and visualize changes in the sociolinguistic landscape of Ukrainian society between 2013 and 2017.

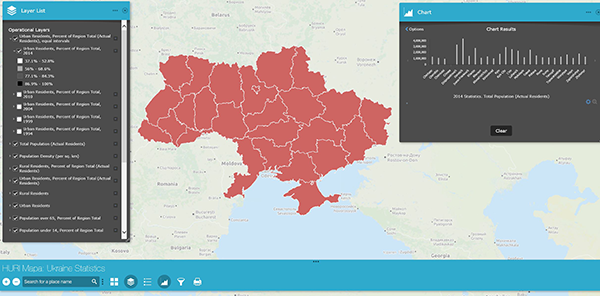

In the 'Statistics' module, we aim to visualize a number of demographic, social, economic, and political variables and see how they evolved during the key years of presidential elections in Ukraine (1994, 1999, 2004, 2010, and 2014). Over the years, numerous scholars have hypothesized the correlation between specific regions (oblasts), identity, and political outcomes in Ukraine. With the help of these maps, we hope to deepen this discussion and further investigate the changing relationship between politics and the regions of Ukraine.

In the 'Statistics' module, we aim to visualize a number of demographic, social, economic, and political variables and see how they evolved during the key years of presidential elections in Ukraine (1994, 1999, 2004, 2010, and 2014). Over the years, numerous scholars have hypothesized the correlation between specific regions (oblasts), identity, and political outcomes in Ukraine. With the help of these maps, we hope to deepen this discussion and further investigate the changing relationship between politics and the regions of Ukraine.

On December 1, 1991, 92.3 percent of the citizens of the newly established Ukrainian state (voter turnout was 84.18 percent) supported the Declaration of Independence, adopted a few months earlier by the Ukrainian parliament. These results included 83.86 and 83.90 percent of voters in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine supporting independence, from a total voter turnout of 80.65 and 76.73 percent respectively (in the Crimea 54.19 percent supported independence out of the 67.50 percent of those who voted). How has this allegiance to independent Ukraine changed over the last two-and-a-half decades? The 'Ukraine and Russia: together or apart?' modules aims to address this issue.

On December 1, 1991, 92.3 percent of the citizens of the newly established Ukrainian state (voter turnout was 84.18 percent) supported the Declaration of Independence, adopted a few months earlier by the Ukrainian parliament. These results included 83.86 and 83.90 percent of voters in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine supporting independence, from a total voter turnout of 80.65 and 76.73 percent respectively (in the Crimea 54.19 percent supported independence out of the 67.50 percent of those who voted). How has this allegiance to independent Ukraine changed over the last two-and-a-half decades? The 'Ukraine and Russia: together or apart?' modules aims to address this issue.

Using a unique and previously untapped dataset of telegrams sent to student hunger strikers in Soviet Ukraine, the 'Revolution on Granite' module examines spatial dispersion of civil resistance in a repressive political regime. The study argues that national identity, compared to socioeconomic grievances, explains better the level of opposition in a multiethnic, authoritarian state.

Using a unique and previously untapped dataset of telegrams sent to student hunger strikers in Soviet Ukraine, the 'Revolution on Granite' module examines spatial dispersion of civil resistance in a repressive political regime. The study argues that national identity, compared to socioeconomic grievances, explains better the level of opposition in a multiethnic, authoritarian state.

To facilitate this scholarship, web maps present geographic information in an interactive display that can be used to tell stories and answer questions. Each one includes a basemap, layers, an extent, a legend, charts, queries, and navigation tools, such as zoom, pan, place finders, and bookmarks. A basemap gallery lets users switch between different maps underlying the data, and pop-up windows display the attributes of specific features.

Users can turn data layers on/off using checkboxes. All layers are turned off by default.

Note: The hosting platform - ESRI's ArcGIS Online Web AppBuilder - automatically detects your web browser language preference and then presents the appropriate language. Although the application was built in English, a localized map viewer user interface will provide instructions and menu links in a localized language.

Web Map Layers Include

With over 100 map layers available, there are countless ways of viewing and filtering Revolution of Dignity Web Map data. The following is a small sample of the layers:

-

Donbas and Crimea

- Attitude toward Crimea

- Cultural and historical closeness to Donetsk

- Russia is an aggressor: yes or no

- Registered IDPs

-

History and Identity

- Maidan and Antimaidan

- Annexation of Crimea and ATO

- Decommunization

- Holidays

-

Language

- All citizens should know Ukrainian

- Importance of Russian for the region

- Native language: Ukrainian

- Language for reading books

-

Religion

- Religious Organizations per 100,000

- Ways of Possible Church Unification

- Confessional Belonging

- Belonging: Simply Orthodox